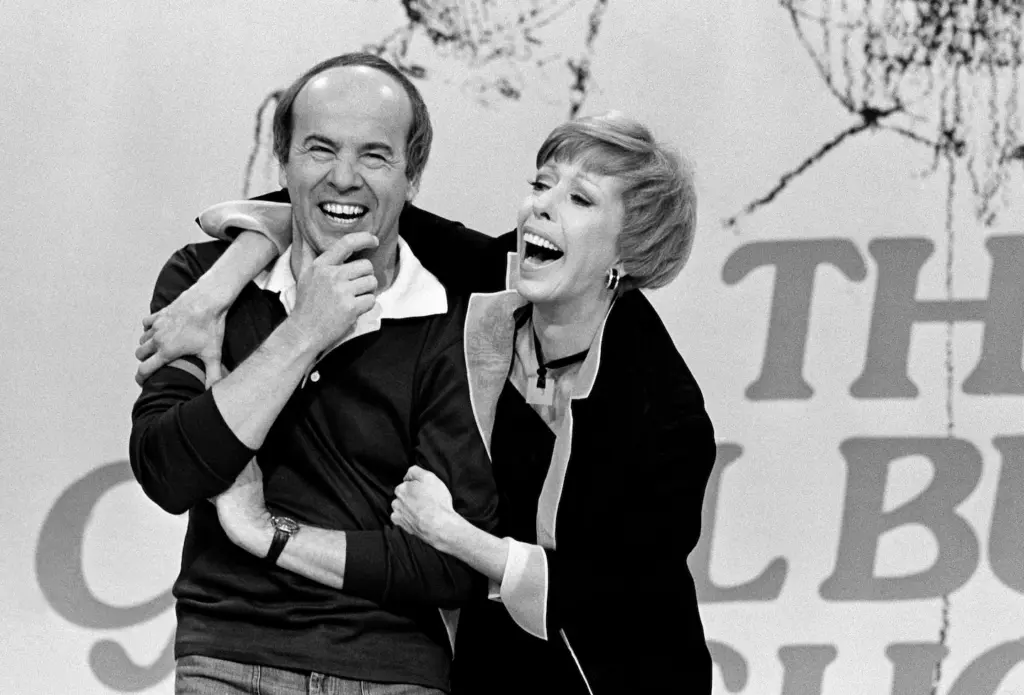

Under the bright studio lights of The Carol Burnett Show, a program already celebrated for its warmth, spontaneity, and unmatched ensemble chemistry.

One comedy sketch emerged that would become legendary not because of elaborate writing or flashy visuals, but because of something far more difficult to master: timing taken to its absolute extreme.

Fans would come to know it affectionately as “Tim Conway Is the World’s Oldest Doctor,” a sketch that perfectly encapsulates everything that made Conway a once-in-a-generation comedic talent.

At its core, the sketch is deceptively simple. There are no complicated storylines, no elaborate costumes, and no elaborate set changes. Instead,

it unfolds in a modest living room, the kind of ordinary setting that allows comedy to breathe without distraction. Harvey Korman plays a seriously ill patient, confined to his home and clearly suffering.

He anxiously awaits a house call from his trusted physician, hoping for swift relief and professional reassurance. From the very beginning, Korman’s performance establishes urgency.

His posture is tense, his voice edged with discomfort, and his expressions suggest a man whose condition is worsening by the second.

This sense of desperation is crucial, because it sets the stage for what comes next.

When the door finally opens, the audience expects the arrival of a capable doctor ready to act. Instead, they are introduced to the physician’s father, portrayed by Tim Conway — and in an instant, the sketch pivots from conventional sitcom pacing to something almost surreal.

Conway enters bent nearly double, his spine curved as though shaped by centuries rather than decades. His movement is astonishingly slow, so slow that it immediately disrupts the audience’s sense of time.

Laughter erupts before he even speaks.

What makes this entrance so effective is not simply that Conway is “acting old,” but that he commits to the bit with absolute seriousness. His steps are tiny, deliberate, and painfully cautious, as if each movement requires negotiation with gravity itself.

One foot lifts, hovers, trembles, and finally settles — only for the process to repeat. Seconds stretch into long, unbearable moments. The audience begins laughing not just at what they see, but at how long they are forced to watch it.

This is where Conway’s genius truly reveals itself. Many comedians rush toward punchlines. Conway does the opposite. He weaponizes delay.

As Conway inches his way into the room, the camera repeatedly cuts to Harvey Korman, whose reaction becomes an essential part of the comedy.

Korman turns away from the audience, bites his lip, and covers his face with his hand, visibly shaking as he struggles to maintain composure.

These moments are not scripted exaggerations — they are genuine attempts by a seasoned professional to avoid breaking character on live television.

The tension between Conway’s relentless slowness and Korman’s barely contained laughter creates a second layer of comedy that the audience eagerly feeds on.

Importantly, The Carol Burnett Show was filmed before a live studio audience, and this energy plays a critical role in the sketch’s success. Every laugh fuels Conway’s performance.

Rather than speeding up, he slows down even more, fully aware that the audience is both suffering and delighted. Each pause becomes longer than the last.

Each movement feels like a challenge: how much can he stretch this moment before it collapses entirely? When Conway finally reaches Korman’s character, the sketch could easily resolve itself. Instead, it escalates.

The examination begins, and what should be routine medical procedures turn into extended physical ordeals. Conway bends forward to listen to the patient’s chest, a motion that unfolds at an almost geological pace.

His hands shake violently, his breathing becomes labored, and his balance appears perpetually on the verge of failure. The act of bending down becomes a full comedic sequence, complete with false starts and prolonged hesitation.

Standing back up is even worse.

Here, Conway demonstrates an extraordinary understanding of physical storytelling. He barely speaks. Dialogue is almost irrelevant.

Instead, he relies on facial expressions, strained grunts, wheezing breaths, and impossibly long silences. These pauses are not empty;

they are carefully calibrated beats that allow anticipation to build until laughter becomes unavoidable. Every second he delays is another punchline waiting to land.

Meanwhile, Harvey Korman’s character descends further into panic. His illness seems less threatening than the possibility that this doctor might never finish a single movement.

His eyes widen with fear, his body stiffens, and his voice carries a mix of desperation and disbelief. The contrast is perfect: one man racing against time, the other seemingly untouched by it.

This dynamic highlights why Korman was Conway’s ideal scene partner. Korman’s reactions are precise and emotionally grounded, giving Conway’s absurdity something real to push against.

Without Korman’s visible distress and mounting frustration, the sketch would lose much of its impact. Together, they form a comedic balance that feels both chaotic and perfectly controlled.

What makes “The World’s Oldest Doctor” especially remarkable is that it represents the height of a particular era of television comedy — one that valued performers’ instincts as much as written material.

The Carol Burnett Show famously allowed room for improvisation and encouraged performers to follow what worked in the moment.

Conway was known for quietly introducing unexpected elements into sketches, forcing his co-stars to react in real time. This sketch exemplifies that philosophy at its best.

As Conway continues his examination, the audience realizes that the joke is no longer just about an old man being slow. It becomes a meditation on patience, endurance, and the sheer absurdity of waiting.

Conway transforms slowness — something most performers fear — into the central engine of the comedy. He proves that restraint, when used intelligently, can be far more powerful than exaggeration.

Decades later, this sketch remains one of the most shared and celebrated moments from The Carol Burnett Show. It is frequently cited as a prime example of Conway’s mastery of physical comedy and Korman’s unmatched ability to react truthfully under pressure.

More importantly, it stands as a reminder of a time when television comedy trusted its performers to hold silence, stretch time, and let laughter grow naturally rather than forcing it.

And this is only the beginning of what makes the sketch unforgettable.

As the sketch progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that “The World’s Oldest Doctor” is not simply a showcase of exaggerated age or physical frailty.

It is, instead, a precise demonstration of how comedy can be built almost entirely from absence — the absence of speed, the absence of dialogue, and the absence of resolution.

Tim Conway turns stillness and delay into a kind of living sculpture, shaping time itself into a comedic tool.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the sketch is how confidently Conway resists the instinct to “help” the audience. At no point does he rush to reassure viewers that a joke is coming.

He allows discomfort to linger. The audience waits, laughs, waits again, and laughs even harder. In doing so, Conway proves a core truth of classic comedy: laughter often comes not from what happens, but from how long it takes to happen.

This approach requires extraordinary control. Any miscalculation — one pause too long, one movement too short — could cause the momentum to collapse.

Conway, however, operates with almost surgical precision. Each delay feels intentional. Each breath, tremor, and pause is placed exactly where it will provoke the strongest response.

The longer he prolongs a simple task, the more the audience becomes complicit in the joke, leaning forward, anticipating the inevitable release.

Harvey Korman’s role grows even more essential as this tension builds. His reactions evolve from impatience to alarm, and eventually to near existential dread.

He is no longer just a sick man awaiting medical care; he is a man trapped in a situation where time has betrayed him.

His expressions suggest that he may never receive help — not because the doctor is incompetent, but because the doctor is simply too slow to exist in the same reality.

What elevates the sketch beyond simple slapstick is the sincerity of Korman’s performance. He never winks at the camera. He never acknowledges the absurdity directly.

Instead, he reacts as a real person would if faced with such an impossible scenario. This commitment grounds the sketch, making Conway’s exaggerated physicality feel even more extreme by contrast.

Importantly, The Carol Burnett Show thrived on this exact kind of chemistry. The cast trusted one another completely, allowing moments to spiral naturally rather than forcing them back into rigid structure.

Carol Burnett herself famously encouraged breaking character when laughter became uncontrollable, recognizing that these unscripted moments often became the most memorable.

Conway, in particular, was known for pushing scenes just far enough to destabilize his fellow performers without derailing the sketch entirely.

“The World’s Oldest Doctor” is a perfect example of this delicate balance. Conway never breaks character, even as those around him visibly struggle.

This contrast — one performer utterly committed, the other barely surviving — amplifies the comedy. Viewers are not just laughing at the character; they are laughing at the shared human experience of trying, and failing, to remain composed.

As the examination drags on, the sketch subtly transforms into something almost philosophical. Time becomes elastic. The audience becomes acutely aware of every second passing.

What would normally be considered dead air becomes the loudest element in the room. Conway proves that silence, when used correctly, can be louder than any punchline.

This mastery places Conway firmly in the lineage of great physical comedians. Like Buster Keaton, he understood restraint. Like Charlie Chaplin, he knew how to make the body speak.

Yet Conway’s style remains uniquely his own. He is not graceful; he is deliberately awkward. He does not glide through space; he battles it. His comedy is built on friction — between movement and stillness, urgency and indifference, expectation and delay.

The sketch’s enduring popularity is also a testament to its accessibility. It requires no cultural context, no topical references, and no prior knowledge of the show.

Anyone, regardless of age or background, can understand the humor of waiting too long for something that should be simple. This universality is one of the reasons the sketch continues to circulate decades later, finding new audiences through reruns and online clips.

Equally important is the way the sketch reflects a broader philosophy of entertainment from its era. During the height of The Carol Burnett Show, television comedy often prioritized performers over premises.

Writers provided strong foundations, but it was the actors’ instincts that brought sketches to life. Conway’s performance exemplifies what happens when a comedian is trusted to follow their own rhythm.

Modern comedy, often driven by rapid pacing and dense dialogue, rarely allows such space. Jokes are delivered quickly, scenes move rapidly, and silence is often treated as a problem to be solved.

“The World’s Oldest Doctor” stands as a quiet rebuttal to that approach. It reminds audiences that slowing down can sometimes produce a deeper, more lasting laugh.

The sketch also reinforces the importance of partnership in comedy. Conway’s brilliance would not shine as brightly without Korman’s reactions, just as Korman’s reactions would lack context without Conway’s relentless slowness.

Their performances are interdependent, each strengthening the other. This mutual reliance is the hallmark of great ensemble work and one of the defining features of The Carol Burnett Show.

Beyond its technical achievements, the sketch endures because it feels joyful. There is no cynicism, no cruelty, and no mean-spirited edge.

The humor arises from exaggeration and shared experience, not from mockery. Even Conway’s portrayal of extreme old age is rooted in absurdity rather than ridicule. The audience laughs not at age itself, but at the impossible scenario created by taking slowness to its absolute limit.

In the years since the sketch first aired, it has become emblematic of Tim Conway’s comedic identity. Fans often cite it when describing his unique ability to derail a scene without breaking it, to command attention without speaking, and to transform the simplest idea into something unforgettable.

It also serves as a lasting reminder of Harvey Korman’s extraordinary talent as a reactor — an actor capable of turning genuine struggle into comedic gold.

Ultimately, “The World’s Oldest Doctor” is more than a memorable sketch. It is a lesson in trust: trust in timing, trust in silence, and trust in the audience’s willingness to wait.

It demonstrates that comedy does not always need to rush forward. Sometimes, the bravest choice is to move at a pace so slow that the world has no choice but to laugh.

Decades later, the image of Tim Conway inching across a living room remains vivid, not because it was loud or flashy, but because it was patient.

In a medium defined by speed and immediacy, Conway chose delay — and in doing so, created a moment of television history that continues to resonate, proving that a painfully slow walk can still carry comedy all the way into legend.