The topic of education is one that rarely goes unnoticed, largely because nearly everyone has opinions about it—opinions on how childcare should be handled, how schools operate.

And what the ultimate goal of the educational system should be. For many, education is not just a part of society; it is the backbone of the future.

After all, the formative years of a child’s life are arguably some of the most crucial. It is during these years that children develop not only the skills necessary to succeed academically, but also the social, emotional, and moral foundations that will guide them through adulthood.

Naturally, then, it is easy to understand why discussions about schools, teaching methods, and parental involvement are so often heated and impassioned. People want the very best for children, and the idea that the system might be falling short can evoke strong feelings.

Yet, while there are countless voices ready to critique schools and teachers, few opinions resonate as loudly and as meaningfully as those coming from someone who has spent decades in the classroom, observing firsthand the daily struggles and triumphs of both students and educators.

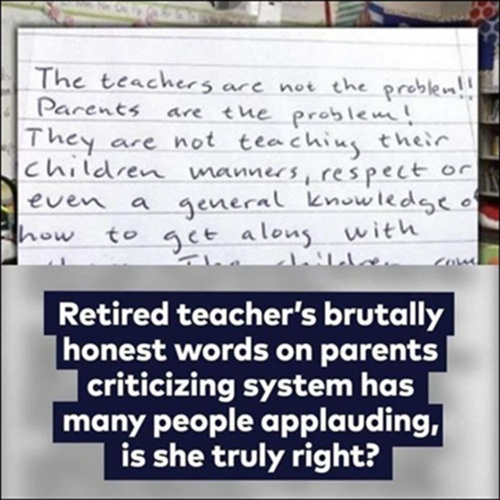

One such voice belongs to Lisa Roberson, a retired teacher whose candid and unapologetic perspective on education went viral several years ago. Roberson’s insights were not drawn from casual observation or anecdotal evidence—they were forged in the crucible of real classroom experience, making her words weighty and difficult to ignore.In 2017, Roberson authored an open letter that was published in the Augusta Chronicle, a regional newspaper with a broad readership. The letter quickly gained traction online and was widely shared across social media platforms, sparking debates and conversations among parents, educators, and policy-makers alike.

Even years later, her commentary remains relevant and continues to be cited whenever the question of school accountability is raised. Importantly, it is necessary to highlight that Roberson’s letter predates the COVID-19 pandemic.

This context matters because much of the discussion surrounding education has since been shaped by the sudden and drastic changes brought on by the global health crisis—changes that included shifts to online learning, hybrid classrooms, and new protocols for student engagement.However, even in light of these massive systemic shifts, the core arguments Roberson made about parental responsibility and student preparedness remain strikingly pertinent. The central thesis of Roberson’s letter is clear: the current challenges faced by schools cannot simply be attributed to teachers or the system at large;

rather, they are deeply connected to the involvement—or lack thereof—of parents in their children’s education. This is a bold statement, particularly in a cultural moment when teachers are frequently criticized as the primary culprits for failing educational outcomes.

By directly challenging this narrative, Roberson turns the lens toward families and invites a more nuanced discussion about accountability. Roberson writes with a tone of frustration but also authority: “As a retired teacher, I am sick of people who know nothing about public schools or have not been in a classroom recently deciding how to fix our education system,” she begins, immediately establishing her credibility. Her perspective is grounded not in hearsay, but in decades of daily experience working with students, dealing with parents, and navigating the challenges of public education.

She goes on to make a point that is as simple as it is profound: “The teachers are not the problem! Parents are the problem! They are not teaching their children manners, respect or even general knowledge of how to get along with others.” The letter vividly illustrates the disconnect between student needs and parental support.Roberson describes scenarios that many teachers encounter regularly: students arriving at school with designer shoes or expensive gadgets, yet lacking the basic tools required for learning, such as pencils or notebooks. She notes with pointed frustration that teachers often step in to provide these essential items out of their own pockets, highlighting the inequities and systemic pressures educators face daily.

Her examples are not meant to shame, but to shed light on a critical reality: no matter how dedicated teachers are, they cannot compensate entirely for the absence of parental guidance and responsibility. Roberson further expands on her argument by addressing the broader consequences of parental disengagement. She urges readers to examine the factors that contribute to schools being labeled as “failing” and redirects attention to the home environment.

“When you look at schools that are ‘failing,’ look at the parents and students. Do parents come to parent nights? Do they talk with teachers regularly? Do they make sure their children are prepared by having the necessary supplies? Do they make sure their children do their homework?” she asks, pointing out that these foundational responsibilities are far too often neglected.

Her words underscore an uncomfortable truth: while schools are institutions designed to educate, they cannot succeed in isolation. The partnership between parents and teachers is essential, and when one side fails to fulfill its role, the consequences are inevitably felt in the classroom.

Roberson also highlights the role of students themselves in the learning process. She questions whether students take notes, complete homework, and actively participate in their own education, or whether they are instead contributing to classroom disruptions.

By emphasizing student accountability alongside parental responsibility, she presents a holistic view of the challenges faced by schools. Education, she implies, is a shared responsibility that cannot be successfully managed by teachers alone.

The letter, published on Thursday, February 16, 2017, and originally posted by journalist Tony Flowers, is striking for its combination of candid criticism, concrete examples, and heartfelt advocacy for children’s welfare. It does not merely assign blame; it encourages reflection and action.

Roberson’s argument invites parents to engage more deeply with their children’s education, to attend school events, communicate with teachers, and instill values and habits that will support their academic and personal growth. In doing so, she challenges a societal tendency to place the burden of educational outcomes solely on schools and teachers, reminding readers that lasting improvement requires collective effort.

Roberson’s candid letter did more than stir local conversation; it ignited debates on a national scale about the true roots of educational challenges in the United States. Her insistence that parents bear a significant share of the responsibility for their children’s academic and social development challenged long-standing narratives that often place the onus entirely on teachers or school administrations.

By doing so, she opened the door to critical reflection: what does it really mean to support a child’s education, and who is accountable when children fall behind? One of the most striking aspects of Roberson’s commentary is her emphasis on tangible parental actions—or in many cases, inactions—that directly affect a student’s ability to succeed.

She points out that attending parent-teacher conferences, maintaining open communication with educators, and ensuring children come to school prepared with the proper materials are not optional; they are foundational. These basic responsibilities, she argues, are often overlooked.

When children arrive unprepared, without the supplies necessary to participate fully in class, or when parents fail to engage consistently with teachers, the educational experience is compromised. Roberson does not shy away from naming these issues plainly, noting that some parents are too focused on appearances or material possessions, rather than the core needs of their children.

She writes: “The children come to school in shoes that cost more than the teacher’s entire outfit, but have no pencil or paper. Who provides them? The teachers often provide them out of their own pockets.” The implications of this observation are profound.

Teachers, she contends, are overextended—not because of a lack of dedication, but because the support structures necessary for effective education are often absent. A classroom where students consistently lack basic supplies, or where homework is neglected because it is not monitored at home, is one where even the most skilled teacher will struggle to succeed.

Roberson highlights the unfairness of this burden: teachers are expected to manage not only instruction, but also the deficits created by parental neglect. In essence, she argues that expecting schools to “fix” these problems without parental involvement is both unrealistic and unsustainable. Roberson also emphasizes the critical role of social and emotional education.

She points out that manners, respect, and the ability to collaborate effectively with peers are learned behaviors, and these lessons often begin at home. When parents fail to model or reinforce these behaviors, teachers are left to fill in the gaps, often with limited resources and time.

The consequences extend beyond individual students; they affect the classroom environment as a whole. Disruptions, disrespect, and inattentiveness can derail lessons, lower overall engagement, and create a cycle where both teaching and learning suffer. Her perspective serves as a reminder that education is not solely about curriculum or standardized test scores; it is also about shaping well-rounded individuals capable of contributing positively to society.

Another important dimension Roberson addresses is communication between schools and families. She argues that consistent, proactive communication is crucial. Parents who do not respond to phone calls, emails, or messages from teachers, or who fail to attend scheduled meetings, inadvertently weaken the support network that students rely upon.

Roberson’s observations highlight that accountability must be shared: schools provide the environment and instruction, but parents provide reinforcement, oversight, and encouragement. Without these components, the system cannot function optimally.

The public reaction to Roberson’s letter was swift and intense. Many readers resonated with her message, applauding her honesty and valuing her perspective as someone who had seen the inner workings of classrooms for decades. Some parents admitted to recognizing gaps in their own involvement and began considering how they could better support their children.

Others, however, reacted defensively, arguing that socioeconomic disparities, underfunded schools, and systemic inequities were more to blame than parental behavior alone. These debates reflect the complexity of educational challenges in America: multiple factors—social, economic, and cultural—intersect to shape student outcomes.

Yet, even amidst these debates, Roberson’s core argument remains influential: parents cannot abdicate responsibility for their children’s learning and social development and expect schools to compensate entirely. In many ways, Roberson’s letter anticipated issues that became even more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When schools shifted to remote and hybrid learning models, parental involvement became more critical than ever. Students relied heavily on guidance and support at home, and parents who were unable or unprepared to assist often saw their children struggle academically and emotionally.

In hindsight, her message about the indispensable role of parents in education resonates with even greater urgency, reinforcing the notion that effective learning requires a partnership between teachers, students, and families. Ultimately, Roberson’s words underscore a timeless truth: education is a shared endeavor.

Teachers cannot teach effectively if students arrive unprepared, disengaged, or unsupported at home. Parents cannot assume that schools alone will instill discipline, respect, or a love of learning. And society as a whole must recognize that the responsibility for nurturing future generations extends beyond classroom walls.

By drawing attention to these realities, Roberson provides a blueprint for constructive action. She does not merely criticize; she advocates for accountability, collaboration, and investment in children’s success at every level. Her letter, though written in 2017, continues to inspire reflection among educators, parents, and policymakers alike.

It reminds us that while debates over curriculum standards, funding, and teacher evaluation are important, the foundation of educational success often lies in the daily choices and commitments made within the home.

Children who are consistently supported, encouraged, and held accountable by their parents are far more likely to thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

Conversely, when that support is absent, schools face an uphill battle that no teacher, no matter how skilled or dedicated, can fully overcome. In conclusion, Lisa Roberson’s viral open letter is more than a commentary on the state of public education—it is a call to action for parents and society at large.

It challenges assumptions, confronts uncomfortable truths, and highlights the vital role that families play in shaping the next generation. The lessons she imparts are simple but profound: show up, stay engaged, communicate, provide support, and reinforce the values and skills that children need to succeed.

Until parents step up and do their part, Roberson warns, schools alone cannot solve the challenges they face. Her message continues to resonate today, encouraging meaningful dialogue, self-reflection, and proactive engagement in the shared mission of educating and nurturing children for a brighter future.